Sunday, October 16, 2005

October 16, 1978

The weekend that His Holiness passed away, memories of long-ago thoughts, of people long-removed, yet omnipresent, flooded over me.

Dolores, this is for you.

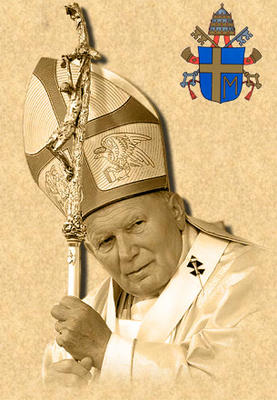

IN MEMORY OF POPE JOHN PAUL II (1920 – 2005)

VIGOR

BY GEORGINA MARRERO

It’s raining outside.

Soft, at first:

Then torrents.

Then soft, again:

Then torrents.

The air is sweet.

Softly filled with the smell

Of the green grass

As it fills my nostrils

On this special day—

Vigor incarnate is leaving us.

Vigor as soft, sweet,

And torrential

As the rain as it descends

Upon the green grass—

As the vigor that helped

Lead us to the green grass…

Of Freedom.

Saturday, April 2, 2005

OCTOBER 16, 1978

BY GEORGINA MARRERO

On October 16, 1978, I climbed into my little Miami blue Volkswagen Rabbit outside my apartment at 1675 Massachusetts Avenue in Cambridge, and drove the nine or so miles to the Ezra C. Fitch School in Waltham. A bilingual teacher with all my credentials in place, I was, nonetheless, considered to be a tutor.

So was Mrs. Dolores O'Brien. In a warm, cozy, wood-paneled basement room congenially divided in the middle by bookcases, Dolores and I carried out our mission as Title VII tutors: she, as the English as a Second Language instructor; and I, as her Spanish Language and Culture equivalent.

No matter: we were two sides of the same coin, mixing, matching, and interchanging children over the course of the school day.

I'd arrived in the Boston area three years earlier. Although I had lived in New York for the three years prior to that, there's something about Boston that screams out, Irish. Perhaps it's the Kennedy legacy? Perhaps it's the Celtics… or now, more proudly than ever, the Red Sox?

Whatever it was, all I knew, back in 1978, was that a sea of Irish surrounded me, a little Cuban-American hybrid. Beginning, of course, with Mrs. O'Brien, her stories of her husband, Bob, and her daughters. I remember one was named Siobhan.

Dolores had been very warm and welcoming from the very beginning. We shared children, resources, funds-even an amused tolerance for our-as it turned out-less than scrupulous boss. She could always get a chuckle, a laugh, or even a hearty guffaw, out of me.

We decorated the room together, yet separately, in a happy style conducive to making our little Kindergartners through sixth graders feel at home. While I cluttered my side of the room with as many bilingual, bicultural visuals as I could get my hands on, I remember Dolores always had a calendar going. One with foliage, one with pumpkins, one with Santa Claus, one with flowers… and, of course, one with shamrocks.

For Mrs. O'Brien, of course, was Mrs. O'Brien. And, of course, there was also her good friend and co-conspirator, Mrs. Anna McMenimen. Mrs. McMenimen happened to be the school secretary, so Dolores was always in the know. Which meant that I was often privy to their flow of sometimes gentle, and sometimes picaresque, gossip.

Much of this gossip often centered on Miss Mary Furdon, our often exasperated, and much beleaguered principal. Exasperated is the operative word, here: if not Miss Furdon, then Anna. At least I knew how to approach Miss Furdon when I had to.

I have a super picture of the four of us and another teacher named Joyce, I think. Judging from the Santa Claus calendar in the background, one of the lovely, extremely artistic fraternal twins from Puerto Rico who graced our classroom as our student teachers during the fall of 1978 took that picture some time in December.

The Suarez twins might or might not have been there October 16, but Dolores and I were. It was a Monday.

News didn't travel as fast then, but I'm sure we heard while we were at school that day: Habemus Papam. We have a Pope: Karol Wojtyla.

A Polish Pope? I remember asking myself. Everyone was shocked-not just the Italians. I'm sure our little group at school discussed it.

Then I returned home to Cambridge and probably listened to the TV coverage. I may have been young - 24 at the time - but not that young that it didn't sink in.

A Polish Pope. What would it mean?

I hadn't really paid much attention to Popes, especially as a young child. After all, I was baptized at age four so that Castro wouldn't send me to Russia, along with other "unwashed" children. My equally hybrid parents didn't think of it, until then.

But they then rushed to include me as a little, yet significant, "aside" in the more "normal" baptism of my godparents' newborn daughter.

And, when we arrived in the States, I duly went to Catechism and celebrated my First Communion when I was eight. I still remember being terrified before my first - and only - Confession.

I also remember that the Pope at the time was a rotund man named John XXIII. Hard to forget, for me: XXIII. 23. My number.

The date was May 12, 1963. The Pope passed away just under four weeks later, on June 3, 1963. I'd been born during Pius The Twelfth's Papacy, but Pope John had been both my Baptism and First Communion Pope. So now, who?

I remember Paul VI as a slender, serious-looking, scholar. As I sporadically attended Mass, especially when I was directed to while I attended summer camp, I also, only sporadically, paid attention to him. But whenever I did, I gave him my full respect.

When he passed away and John Paul I ascended to the Throne of St. Peter, I was about to begin my second year as bilingual tutor at the Fitch School. Thirty-three days later - September 28 - was a Thursday. We must have heard the news of the new Pope's sudden demise while at school that day, too.

What was going on? I probably figured he had been infirm. Was the Vatican aware of his condition? I'm asking myself that, now, on the heels of learning about the conspiracy theories that surround his death.

The school was abuzz. I'm sure I sat in on many a discussion between, especially, Mrs. O'Brien and Mrs. McMenimen.

But here we were. The Conclave of Cardinals had reconvened, and a Pole named Karol Wojtyla had been named the new Pontiff. I remember the coverage about how to pronounce-let alone, spell-his name. John Paul II soon became much easier to handle.

What would it mean? We quickly found out. The new Pope visited his homeland. Solidarity. Lech Walesa. President Reagan: "Mr. Gorbachev, tear down this wall." I visited my aunt and uncle in a free Romania.

I now paid attention, albeit at a respectful distance.

Pope John Paul II ascended to the Papacy when I had just turned twenty-four. Twenty-six plus years later, he's gone. He will have been the Pope of my youth to early middle age.

Although I have never formally confessed, nor taken Communion, since my First Communion, there is a bond I have never been able to loosen. I remember only The Lord's Prayer, so I have to mumble along whenever I attend Mass, mimicking others. And yet…

… I could not help not taking note of the date - October 16, 1978 - when Karol Wojtyla became Pope.

And I could not help remembering where - and with whom - I was. With some lovely Irish ladies who were probably providing this hybrid with nourishment I wasn't even aware I was imbibing.

Rest In Peace, Your Holiness.

For Dolores O’Brien. Sunday, April 3, 2005

Tuesday, October 04, 2005

Neither 10/12/02 Nor 10/1/05: My Bali

A five-time visitor to The Enchanted Isle since 1987, the bombings in 2002 and, again, just the other day, hit deep. Here's the first piece I wrote after my third trip, in 1993: Bali and Its People: A Love Affair. Always.

BALI AND ITS PEOPLE: A LOVE AFFAIR

BY GEORGINA MARRERO

The things that I have loved most in my life are often the things I liked least when I was first introduced to them. This is how I feel towards Bali, the small, culture-rich island that is the Indonesian archipelago’s crown jewel. During my first trip there, in 1987, I was mainly preoccupied with what I perceived to be the squalid sights and smells of the place. Appalled by the open sewers, the squat toilets, and the brisk selling – and consumption – of unsavory-appearing morsels, I was even more dismayed by the consistent lack of air-conditioning, hot water, and sometimes even electricity. A healthy dose of “culture shock”: that’s what I was experiencing at the time (although I wasn’t aware of it). On the contrary: I was so overly concerned with my creature comforts that I never really let myself take a good look at the place. However, I did like the smiling, friendly Balinese people even then. Without my realizing it, the seed had been planted for my return.

My second trip, in 1989, proved to be eminently more enjoyable. The streets had been cleaned up a bit; I had (more or less) mastered the use of squat toilets; the electricity no longer disappeared during each and every rainstorm; the food was more appealing, both in smell and in taste; and – most importantly – my eyes were finally opening to the wonders of the place. I now beheld the rice terraces fashioned like stairs into the sides of the hills, stretching as far as the eye can see; the iridescent blue-green lagoon at Candi Dasa; the pink chicken in Tenganan, the Bali Aga (“Old Bali”) village where animals and plants are still worshipped, rather than the Hindu gods; and the women moving in stately procession towards the pura (temple) during festival days, with trays piled high with fruits, flowers, and sweets as offerings to the gods perched daintily – yet precariously – on their heads, while the men gathered at the cock fights. The cremation of a fourteen-year-old boy moved me greatly, as I joined mourners and tourists alike in the solemn, yet joyful, procession. Listening to the gamelan players, and viewing the lighting of the funeral pyre with kerosene, I felt nothing short of awe, watching it burn. This time not only had the Balinese people continued to win me over, but I had also fallen in love with Bali itself. There was no doubt in my mind that I would return.

I returned to Bali in 1993. Accustomed to early summer tourist traffic – when Americans seemed to overrun the island – I discovered that, as mid-to-late summer is European holiday season, many of my fellow paradise seekers now hailed from Germany, France, the United Kingdom, Italy, and Scandinavia. In addition, Aussies always abound, as they have to travel a mere three hours to get to Bali as compared with everyone else’s fifteen to thirty hour treks! A new group of visitors had discovered Bali: the Japanese. There were now busloads of them… with tour guides and cameras in tow.

The influx of Japanese tourists was but one of the many changes that seemed to have taken place in Bali over the course of my four-year absence. The street smells were now virtually non-existent; air-conditioning had become more prevalent; and a brief lack of electricity went for the most part unnoticed. In addition, the airport had been completely refurbished; the highways had been widened to accommodate the increasing number of tour buses and pleasure vehicles; and boiled water (for drinking) was now guaranteed in all but the smallest warung (restaurant).

However, in the midst of all the changes and increased tourism on their island, the Balinese people continue for the most part to lead their lives as they have for centuries. They still prepare and distribute the daily offerings (little baskets made of young coconut leaves, which are filled with flowers, banana leaves topped with a few grains of rice and grated coconut, and with a few incense sticks stuck into the baskets before they are lit to release their fragrant scent right before they are distributed in front of entranceways, statues, and wherever else custom dictates). They still cremate their dead, usually in mass cremations where often no fewer than eight to ten funeral pyres are lit. A wondrous spectacle to behold, made even more so by the Hindu belief that those being cremated will soon be reborn, hopefully having earned a better station in life. They continue to cultivate their rice fields, which from afar look like mirrors in which one can almost see one’s reflection. They dote on their children and grandchildren. They play their gamelans. They weave their ikat cloth. They fashion their carved masterpieces out of ebony, mahogany, sandalwood, and even tree trunks. All of these rituals and skills have been passed down from one generation to the next. They are all but a tiny part of the incredibly rich culture and sense of tradition that these extraordinary people possess.

It is to the Balinese people’s immense credit that they have managed to imperturbably proceed on their well-ordered paths in life, at the same time that they have assimilated only as much of modern-day culture as their needs dictate. Justifiably proud of this accomplishment, a number of the islanders indicated to me that they are, nonetheless, also wistful for the days before bumper-to-bumper traffic on their highways, an increase in crime (primarily theft), land over-development, and mass commercialism. I found myself feeling the same way: during the summer of 1993 I almost craved the dusty streets of old, the wayward electricity, and the undisturbed expanses of land that I remembered from the late 1980’s.

I have a love affair with Bali, and with its people. The island itself is an earthly taste of paradise, to be sure. It is the Balinese themselves, however, who continue to enthrall me. They are a people who are open and caring and who share with you if you share with them. The peasant woman walking along the side of the road with a basket perched precariously on her head still smiles at you if you smile at her. The young shopkeeper is still eager to impress you with her knowledge of English. The artisans still aim to impress you with their skill. The server in the restaurant still beams approvingly when you finish your plate. Five times, and counting: I’m not finished with you, yet.

Revised 2003 version of original 1993 manuscript 1075 words All rights reserved